By Sheila Adogola

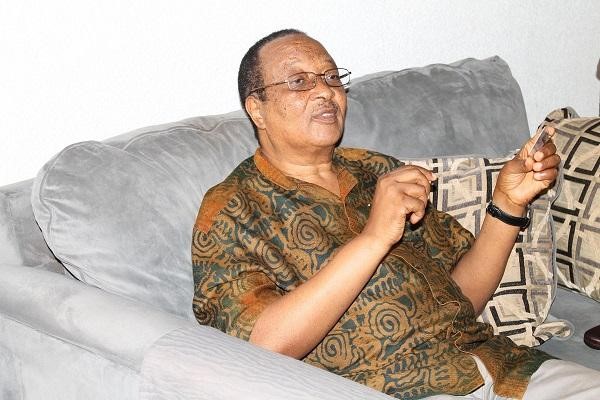

On 28th May, a great man and icon to the nation, Prof. Apollo Nsibambi, was lost. During a requiem mass on 3rd June at Namirembe Cathedral, his heiress, Rohda Nakimuli Kasujja, was made known.

Applause came from women’s empowerment activists on the decision, who called it a heroic act and a great channel through which women’s empowerment could be advocated, specifically, through which amendments to the Succession Act in order to ensure inheritance is not limited to men could be made.

The declaration also brought about criticism from the Buganda community who did not acknowledge the act, because in Buganda culture, the lineage and blood ties are passed on through patrilineal lines in order to preserve their culture from generation to generation thus a woman cannot carry them on because she gets married and attains another name.

Inheritance in Uganda is governed by the 1906 Succession Act and Administrator General’s Act, which proclaim that a customary heir should be a person recognized by the rites and customs of a tribe or community of a deceased person as being a customary heir of the deceased.

Ugandan law protecting women’s rights to inheritance is not often effective due to the influential nature of the cultural laws and if we attach inheritance to only property and not consider other aspects, chances are that entire lineages and bloodlines could be lost in the process.

Is there a possibility that culture and law can harmonize and work hand in hand in order to end such discriminatory practices?

Can provisions be made to name an heir that will carry on the lineage and blood ties while the heiress, as already identified, is allowed to oversee the property left by the late?